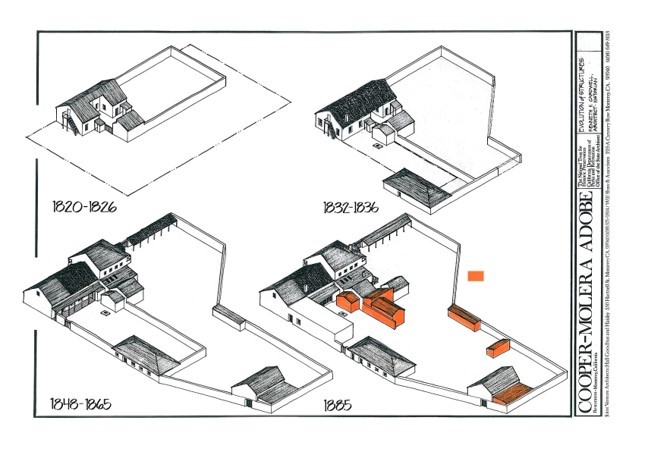

The Evolution of the Cooper Adobe Complex

In 1827 Captain John Rogers Cooper was baptized into the Catholic faith and adopted his Mexican name of Juan Bautista Rogers Cooper. In August of that same year he married Maria Encarnacion Vallejo. It was time to build a house for his new wife and future family.

Captain Cooper applied to the town council (ayuntamiento) for a building lot. His petition was approved in 1832, for a piece of property described as, “…a lot adjoining the zanjon (gulch) and the front of Amesti’s house…with a frontage of 50 varas (approximately 137 feet) and a depth of 90 varas (approximately 247 feet).” Cooper built a one story adobe house with the help of George Kinlock, a skilled ship and house carpenter. Construction materials were found locally. The foundations were made of a yellowish-white sedimentary rock, locally called “chalk rock” or “Monterey Shale”. Heavy, black native earth was used to construct the thousands of adobe bricks needed for the walls. Lumber for the roof beams and rafters was cut from pine and redwood forests outside of Monterey and in the Santa Cruz mountains.

Archaeology Room Exhibit showing the foundation of "Carmel Stone" 2018 © The National Trust for Historic Preservation:

Wealthier residents of Monterey had wooden floors, and this was probably the case with the Cooper adobe. Local clay was used for the heavy, curved roof tiles and lime and sand for plastering the walls, inside and out. Glass, sashes, nails, and miscellaneous hardware either was shipped from New England or the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii).

Although solid and reasonably comfortable, Cooper’s house had few amenities. It did not have an indoor fireplace. Thomas Larkin, Cooper’s half-brother, is credited with installing the first fireplaces in Monterey. His house was constructed three years after Cooper’s. Very little is known about the early furnishings of the house, although it is a safe assumption that it contained very few furnishings and no carpets. Cooking was done in a separate structure. The original adobe kitchen was erected at the same time as the main house.

Today the Cooper adobe is surrounded by gardens, but this was not the case originally. An 1841 visitor to Monterey wrote, “The soil, though light and sandy, is certainly capable of cultivation; and yet there is neither field nor garden.” The adobe’s front door opened directly onto a rutted, unpaved road, dusty in summer and muddy in winter. Monterey had no regular plan, and houses were dotted randomly on the high ground surrounding the harbor. In 1842 Monterey was described as “a mere collection of buildings scattered as loosely on the surface as if they were so many bullocks at pasture so that the most expert surveyor could not possibly classify them into crooked streets.”

Cooper Adobe (Left) and Diaz Adobe (Right) Courtesy of The California History Room, Monterey Public Library

Shortly after construction was finished, Cooper sold the northwestern half of his house to John Coffin Jones. This section of the house had five rooms and a small backyard measuring 40x90 feet. Jones built a separate kitchen and dug a well behind the house. Jones kept the house for three years and then sold the property to Nathan Spear in 1836. Spear used the adobe as his shop and residence. Two years later he moved to San Francisco, leaving his business in the charge of William Warren. Warren continued to run the store and was known as a fine cook. Before long sea captains and supercargoes made his store their rendezvous while in port.

By 1842 a third, large structure occupied the southwest edge of the property. An 1842 lithograph of Monterey identifies the building as “Nathan Spear’s Warehouse.” It is unknown when this building was constructed and if it was constructed by Cooper or Spear. The lithograph also depicts a high wall capped with tiles that surrounds the entire property.

In 1842 Cooper purchased a strip of land lying just behind his garden wall from his neighbor, Gabriel de la Torre. This transaction extended his holdings beyond Nathan Spear’s warehouse, giving him access to what would become Polk Street, and expanded his lot to its present dimensions.

A major remodel of the house started in 1850. With proceeds from the sale of his San Quentin Rancho, Cooper had the means to convert his house to a two-story, Monterey style structure. To allow for the installation of a hallway and stairs to the new second floor, Cooper bought a five-foot wide, 48-foot-long piece of land from Manuel Diaz, the owner of the northwest portion of the property. Diaz had purchased the property from Spear in 1845 for use as a residence and store.

How the Cooper Molera Adobe changed over time

The original adobe walls were raised with additional courses of adobe brick, bringing the building to a full two stories. Front and side balconies overlooked Munras Street and the garden respectively. The odd roof framing – hipped on one side and gabled on the other – may suggest that Cooper planned on acquiring the Diaz adobe as well. It was during this remodel that the skylight room was added to the rear of the adobe, connecting the kitchen with the main house.

Now the Coopers, their six children and Encarnacion’s mother had one of the finest homes in Monterey.

The Cooper family lived in the house until 1864 when they moved to San Francisco, the fast-growing center of American California. When Cooper passed away in 1872, his wife, Encarnacion, became the owner of the adobe and from Encarnacion, the property was inherited by Anita "Ana" Cooper Wohler in 1900. It was Ana who reunited the two sections of Cooper’s original house, separated for nearly 70 years, when she purchased the Diaz section of the building. With the change in ownership came changes to the property. A door was cut through the common wall for access. A high parapet was built along the roofline of the Diaz adobe, to make it look more impressive.

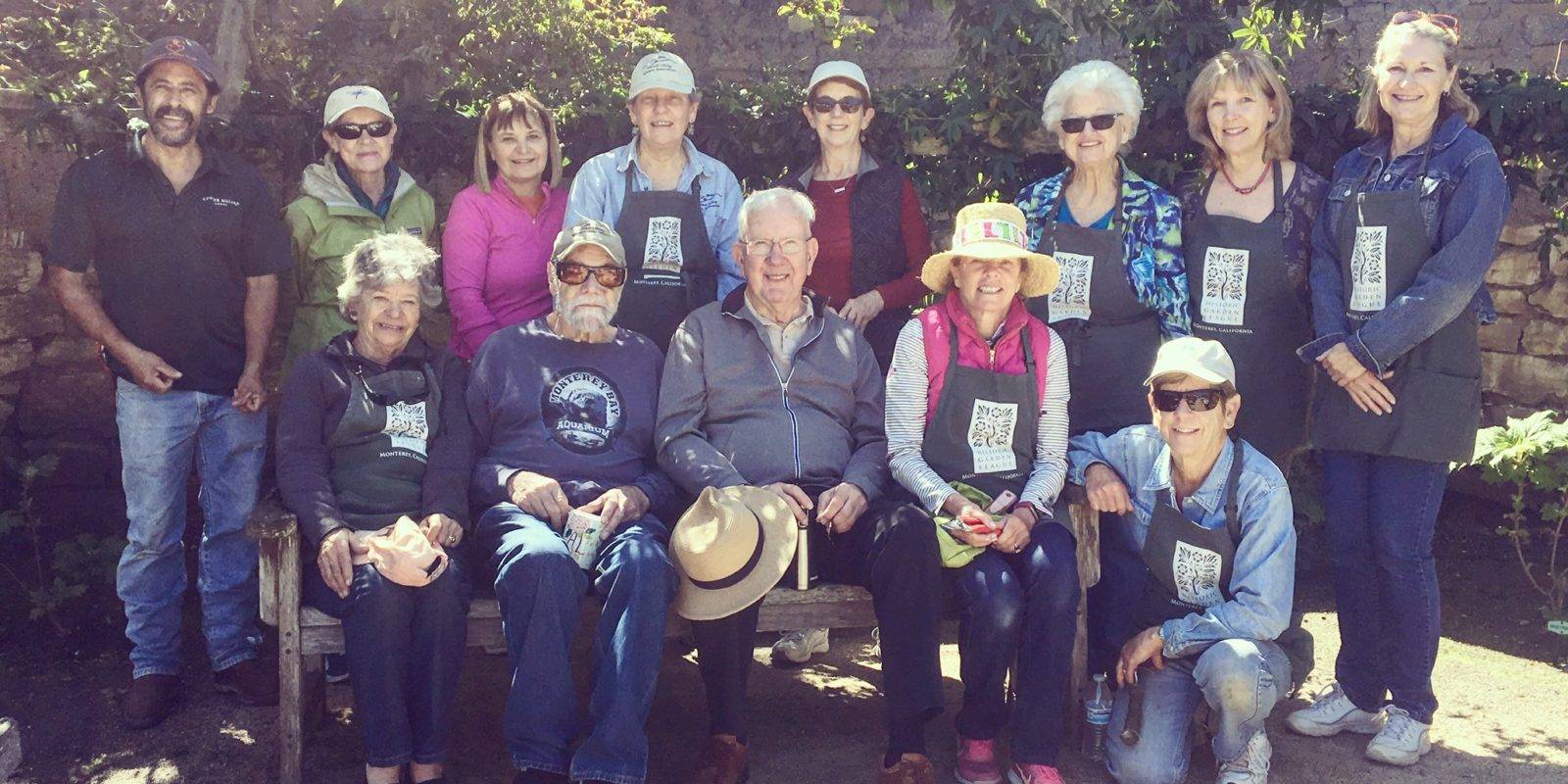

Two wood frame structures were built behind the kitchen, one of which is today’s “Red House”. Andrew Molera used the old adobe intermittently until his death in 1921. Frances Molera continued to maintain the adobe but lived in San Francisco. When she died in 1968, she gave the property to the National Trust for Historic Preservation. The Trust leased the property to California State Parks and the first major renovation of the property commenced. Four decades later, the National Trust took over the operation of the property and a second major renovation of the property was completed. Today the gardens, adobe museum and commercial partners welcome visitors to this unique survivor from Alta California’s past.